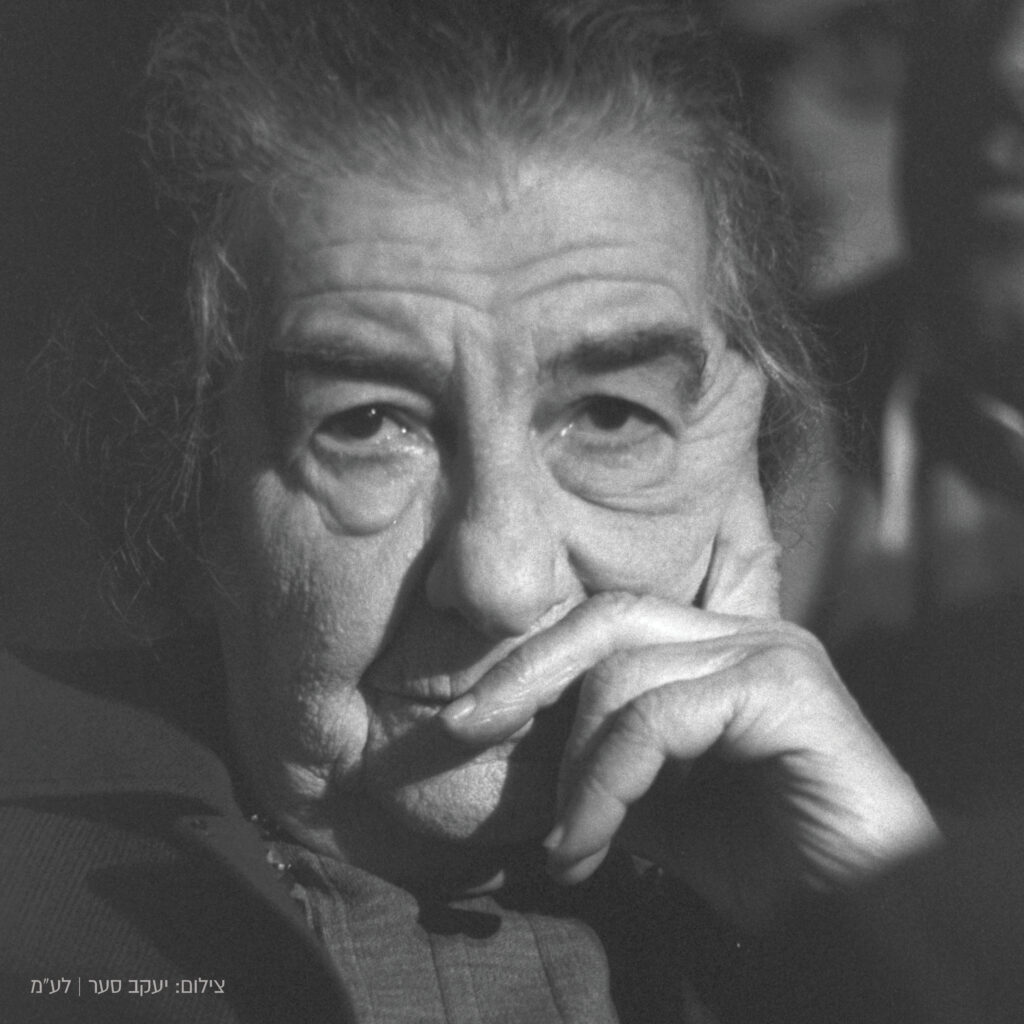

Since the Yom Kippur War in 1973, the dubious title of “Worst Prime Minister in the History of Israel” has hovered over the head of the first and only woman to have held that office. Now, 50 years later, it’s clear that the odds were stacked against her from the beginning.

This week commemorates the Yom Kippur War's anniversary, a festering wound in our nation's history. Most of us can readily recall the familiar narrative: the nation's euphoria after the Six-Day War and the grave oversight that cost thousands of lives in 1973. The rest of the spiel include a series of angry insults and accusations directed at Prime Minister Meir, although some simply crown her as “the worst Prime Minister in the country's history”.

This year however, that contentious title faced a formidable challenge, in part thanks to Guy Nativ’s new film “Golda”, starring Oscar winning Helen Mirren who stepped into the iconic shoes of ‘the woman and the cigarette’ – the first, and only (thus far) woman to hold the office of Prime Minister of Israel. In fact, she was one of the fourth women ever to head a country, after Indira Gandhi in India and shortly before Isabella Peron in Argentina. And by the way, Indira was the daughter of Nero, the first mythical Prime Minister of India; Isabella was the wife of Juan Peron, himself the President of Argentina. Golda, on the other hand, didn’t ride on the coattails of any male, relative or spouse. The new film depicts her as a deeply conscientious leader, burdened by the weight of her responsibilities, quite contrary to the ruthless and frenzied male leaders that have characterized Israeli politics. In this case, cinema mirrors a shift that has transpired in real life as well.

Over the years, public sentiment has shifted toward holding leaders accountable for their failures. No longer are the bloody scars of war left orphaned without culpability. Many Israelis have learned about the shortcomings of Major General Eli Zaira in overseeing the military intelligence; about Moshe Dayan’s PTSD and about the arrogance, leading to utter paralysis of the military echelon – a generation of officers intoxicated by the fumes of vanity from the Six-Day War.

However, these three men were treated differently in the public eye compared to Golda. This was an era when military generals were celebrated in tabloids as if they were bona fide superstars. Their failure was always relative to hers, and they still enjoyed the prestige of being revered war heroes.

Yet, Golda remained an exception. Her cabinet office earned the disparaging moniker “the Kitchenette,” her choice of footwear was a household topic, and unlike all the other preceding and succeeding prime ministers (except for Netanyahu), she was addressed in the media by her first name, as if she was their grandma’s sister, and not, say, the head of their country’s government. Her esteemed roles in the pre-state era held no sway in the male-dominated cabinet, replete with battle-hardened veterans. Not even her role in the “Airlift that saved Israel" during the war, or her vigorous diplomacy could shield her.

Meir went along with the complacency of the military generals. Maybe she felt they were wrong but didn’t dare to speak up. How could she compensate for the damage done? And who could stand against them, with their maps and binoculars, and their smug posture? Although Meir was prime minister, she was also a woman with no military background. And above all, she was a woman among men. A strong woman in an ultra-chauvinist world and militaristic society. Whether she was as bad as they remember her, or whether we were too harsh with her – she may never have stood the chance.